October 13, 2021

Kosky and 1927’s Magic Flute: A complete reinvention celebrates the opera’s roots

Although Melbourne-born director Barrie Kosky has been involved in theater and opera professionally for over 30 years, he didn’t direct The Magic Flute until 2012 when he began as Komische Oper Berlin’s new intendant and artistic director. It wasn’t that the opportunity to direct one of Mozart’s most popular operas had never presented itself: “I’ve always said no to directing The Magic Flute. We all know that it’s very famous and has great music, but it’s just one of those pieces that’s a minefield of problems. It doesn’t reveal itself easily.” When the Komische Oper programmed The Magic Flute as part of Kosky’s inaugural season, he realized that he needed to find a method with which to present the work that would delight audiences while resonating with his artistic vision.

A friend informed Kosky that 1927 — a performance company combining performance and live music with animation and film — was coming to Hannover to present one of its works. “I took myself off to the theater festival; the performance started, and within 30 seconds, I knew that I had to ask 1927 to do The Magic Flute. I thought, ‘This is the way I could do it.’” After the performance, Kosky went backstage and asked the company to participate. The group answered with a question: “What’s The Magic Flute?” Kosky was delighted. “I thought, ‘They’ll be right for the job.’”

Suzanne Andrade, co-artistic director of 1927 and Magic Flute co-director, offered her perspective on the collaboration’s genesis: “The Magic Flute picked us! We agreed, and then we listened to it. After watching clips of some dodgy productions, we immediately thought, ‘What have we agreed to?’ But then we went straight to the source, listened to the music ad infinitum, and fell in love with it. We dreamed up some ideas and let the music do the profound stuff while we did the playful stuff.”

Almost ten years after its premiere, Komische Oper Berlin’s The Magic Flute has been performed in 35 different cities, seen by nearly 700,000 people around the world, and continues to sell out every run when it’s presented in Berlin. Kosky is excited to bring Flute to the Windy City. “I’m very thrilled that we’re able to bring this to Chicago.”

Andrade, animator Paul Barritt, the rest of the 1927 team, and Kosky spent three years creating the production. “The first year and a half involved talking through the whole thing. There was a lot of discussion and we took the entire piece apart line by line, moment by moment,” explained Kosky. Andrade added, “Every idea came from careful listening to the music — not from an academic standpoint or as operatic experts — just as listeners. We sat with the music for such a long time, and it informed every idea.”

As is done when sequencing traditional films, the group put together storyboards; every single concept was borne from the minds of the creative team. The staging uses a computer program to project the opera’s animation, but all imagery was hand drawn by Barritt, who spent about a year creating The Magic Flute’s art. After the team concepted the entire opera, the ensemble began to workshop scenes with singers. It took two months to teach the cast its choreography.

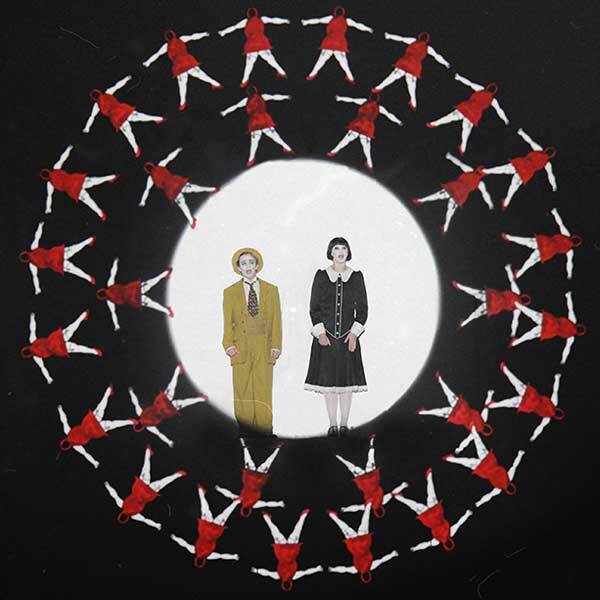

1927 and Kosky’s Flute is an endlessly colorful universe; its many inspirations include silent film, German expressionism, and quirky British humor. Andrade filled in further details about the myriad sources that informed the ensemble’s creativity: “We chose silent film as the starting point for the show; 1927 is hugely inspired by silent film in all of its work. Paul, Barrie, and I also are total magpies. We all read and watch so much, so naturally a mish-mash of influences came through. Edward Gorey has always been a wonderful inspiration for staging. He draws his characters so beautifully — all of them dynamic and composed at odd angles — and he was very inspired by ballerinas. We often use his work in practice with actors to move them away from naturalism.”

The Magic Flute was the last of Mozart’s singspiels, a German operatic form developed in the 18th century. Singspiels include spoken dialogue interspersed with Wieden, of which Schikaneder was director from 1789 until 1801. He was also responsible for the creation of the Theater an der Wien, which opened in 1801 and housed his enchantingly extravagant presentations. “Schikaneder’s theater was a theater of visual effects, like a mixture of vaudeville and pantomime. He was very well known for doing scenic extravaganzas. This is why The Magic Flute is full of effects. That’s part of the nature of this opera. We’ve just sort of found a 21st-century form for what Schikaneder did in the 18th century,” said Kosky.

The Magic Flute wasn’t intended for an aristocratic audience; rather, it was crafted for a public that craved dialogue and theatrical effects. “In a way, it’s a radical piece for Mozart to be involved in; for him to write this opera for Schikaneder’s theater is almost like Mozart writing a Cirque du Soleil show in Las Vegas,” emphasized Kosky. Kosky and Andrade’s Flute nods back centuries. “There is a roller coaster of visual imagery in the piece, which is meant to delight and intoxicate, as Schikaneder did in the 18th century.”

Don’t be misled by the intricate choreography and perfectly timed interactions, however; there is plenty of room for organic artistry and in-the-moment expression in this production. One might think that the music is subservient to the computer system and the timing of the visuals, but it’s actually the reverse: a conductor can take any tempo, and the animation will respond to the music in real time. “Although we have done this seemingly radical staging of The Magic Flute, we never, ever ignored the music,” Andrade assured. “The singers were tantamount. We positioned them around this huge screen and built choreography and animation around them, so they are totally wrapped up in this world and the music, acting, singing and animation all work around each other, in service to one another.” Kosky concurred: “If it weren’t a combination of live singers and animation, it would be dead.”

Andrade, Barritt, and Kosky’s Flute isn’t rooted in reality. “The hybrid of singers interacting with animation means our inspirations get mashed up and thrown around and come out quite different, but with a hint of the familiar... like a weird dream in many ways,” remarked Andrade. This dreamspace is a perfect vehicle for The Magic Flute’s plot, as Kosky feels the piece needs to be presented as a sort of parable. “It needs to have a sort of naïveté and fairytale quality. You cannot stage the subtext — it falls apart. We found a visual language and performance style that mirrors that. If you try to approach Flute in the same way that you approach Don Giovanni or The Marriage of Figaro, you’re doomed to failure. This is a fairytale singspiel, which means you are presenting archetypes and dream images. Things shouldn’t make sense.”

Kosky approaches directing this Flute in an entirely different way than his typical directorial style. He doesn’t normally use video in his productions. “It’s a very different form of theater than what I normally do, which is very psychological. This is choreography. The singers, particularly Tamino, Pamina, and Papagena, have to learn very complicated movements because they are interacting with animations, not themselves. It’s a sort of puppet theater using live singers. The singers are asked to play less psychologically and much more in terms of movement. Anyone who tries to create psychological complexity with this piece is doomed; you can’t do that with fairy stories or mythology.”

1927 and Kosky’s The Magic Flute takes full advantage of opportunities to highlight Mozart’s fantastical characters. Kosky deliberately chose not to trap characters in stereotypes or humanizations. “The only three characters that come anywhere near being human are the hero and heroine of the fairytale Tamino and Pamina, and Papageno.” Both Andrade and Kosky believe Papageno is the central figure in Flute. “He’s the most sympathetic and interesting character in the whole opera.” Andrade declared. “We realized early on that Papageno is the key to the show. The audience has to love him. We took as our inspiration the master of all lovable characters, Buster Keaton. We also gave him an animated cat. When in doubt, add a pet.” In this Flute-world, the Queen of the Night is a bloodthirsty, skeletal spider woman that hurls knives almost as precisely as she sings her high notes. At one point during her famous aria “Der Hölle Rache,” she sends a swarm of baby spiders to overcome Pamina as she lies helpless in the Queen’s web. “The Queen of the Night was a tricky one,” said Andrade. “We decided to abandon any ideas about her transformation from caring mother to monster, and went straight in with ‘mother-in-law from hell.’ Her music is so fabulous, so dramatic, and so well known, that we could not help but paint a picture of an enormous spider queen, all bones, lightning, and black-widow imagery. We had fun with her!”

Each artistic choice also supports the charm and musical nuance of The Magic Flute’s brilliant score. Monastatos’s dogs surge forth on their leashes ready to attack Pamina with the same snarling energy as Monastatos’s pointy, barbed vocal lines. Pamina and Papageno jump rooftop to rooftop, playfully emphasizing Mozart’s jaunty rhythms. The stage-engulfing video projection also is striking in its scenes of simplicity, such as Pamina’s snow-laden “Ach, ich fühl’s,” in which the young woman stands alone beneath a leafless tree, isolated within a snowglobe, desperate for Tamino’s love. Both Andrade and Kosky possess a deep admiration of Mozart’s music and the score of The Magic Flute, which is reflected in every directional decision and visual invention. In the closing scene, music notes sweep across the screen and land atop the chorus. It is an animation that suitably depicts Mozart’s ability to permeate the listener’s very being. “It’s Mozart, so it’s phenomenal. It’s an extraordinary score,” affirmed Kosky. The composer’s gifts extend far beyond his music, however. “The word that I always associate with Mozart is ‘humanity.’ He did not judge his characters; he presents them with flaws. Mozart is one of the only composers who did that,” concluded Kosky. “We don’t live a life like Pamina and Tamino in this fairy story, but when Pamina can’t make Tamino speak to her, her pain is a pain that any of us can feel. That’s Mozart’s genius; he creates something universal from something very specific. That makes him the most humane of all composers.”

Laura Sauer is Lyric Opera of Chicago’s program book editor.

November 3 – 27, 2021

The Magic Flute

The Magic Flute

Mozart’s miraculous blend of the human and the supernatural, comedy and romance, draws us into a world where a prince, Tamino, and a princess, Pamina, triumph over every obstacle in their search for wisdom and enlightenment, and are finally united in love. This is a gloriously varied score, with the lovers’ soulful arias, the stratospheric vocal fireworks of the villainous Queen of the Night, the subterranean depths of the formidable high priest Sarastro, and the folk-like melodies of the lovable birdcatcher, Papageno. Lyric brings you a critically acclaimed production that pays homage to the silent movies of the 1920s, praised by The Guardian as “a joyous yet profound staging in which animation takes centre stage…[taking] live video to new heights on the opera stage.”