April 09, 2021

Attila: Opera vs. History

Attila was the ruler of the nomadic Huns in the fifth century, and his name has become synonymous with that of a ruthless warrior. Throughout history, Attila has been fictionalized in epic poems, in songs performed on The Dick Van Dyke Show, and even written into vampire lore in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Our favorite retelling of this story is, of course, the one with the massive chorus.

Verdi’s Attila tells a story of the Hun’s final days and his failure to conquer Rome. But with a legend as large as Attila, it’s easy for facts and fiction to get mixed up. So what’s true to history and what’s fabricated for drama in this early Verdi opera?

Huns in battle with the Alans, 1870s engraving after a drawing by Johann Nepomuk Geiger

What’s in a name?

In both the opera and in history, Attila the Hun was called “Flagellum Dei,” or “The Scourge of God.” Since most of what we know about Attila comes from accounts written in Greek or Latin by the enemies of the Huns, descriptions of the conqueror range from “scary” to “downright terrifying.”

The power of prophecy

In the opera: In Act One, Attila has a vision where an old man accosts him at the gates of Rome and tells Attila that he will never take the city. The conqueror takes this seriously, and when the old man from his dream turns out to be Pope Leo, Attila swears to give up his attack on Rome.

In history: Attila did believe in prophecy. When a shepherd in his camp found a well-crafted sword and presented it to him, Attila took it as a sign that he had been appointed ruler of the world, and that the sword itself belonged to Mars, the Roman god of war.

The Huns led by Attila, invade Italy, painted by Ulpiano Checa, 1887

Femme fatale

In the opera: Attila is smitten with Odabella, a captured warrior woman from the conquered city of Aquileia. He presents her with his sword and she appears to accept his offer of marriage. In Act Three, when he finds his wife-to-be with a Roman general who’s her real beloved, Attila realizes—too late—that he’s been betrayed.

In history: In 450 A.D., Attila received a plea for help from Princess Honoria, sister of the Western Roman Emperor Valentinian III. She was in an unhappy engagement and sent a messenger to the Hun with a promise of gold and a ring if he would intervene on her behalf. Attila wrongly interpreted this as a marriage proposal and accepted it, as well as half of the Western Empire as her dowry. Honoria did not want to marry Attila, and ultimately married her original beau. Attila responded to this rejection like any spurned lover would and marched on France.

There’s no place like Rome

In the opera: As prophecies tend to do in opera, this one came true. Attila is betrayed by his new lover as Roman troops march on the Hun army, thus ending the brutal rule of Attila the Hun.

In history: Legend has it that St. Peter and St. Paul themselves appeared to Attila and threatened him into settling a deal with Pope Leo I. In reality, a famine had just swept the peninsula and it likely would have been prohibitively expensive to continue the onslaught.

Feast of Attila by Mór Than, 1870 (Hungarian National Gallery)

The Death of Attila

In the opera: Attila is stabbed by Odabella with the very sword he presented to her in Act One. Verdi ties up this plot neatly, delivering Greek tragedy-style justice.

In history: The real story of Attila’s demise might be deserving of its own opera. After he failed to take Rome, the conqueror was found dead on his wedding night. His bride was the beautiful Ildico, and she was one of several wives he had at the time. Of course, it is also possible that Attila died of natural causes. According to the sixth-century writer Jordanes, Attila celebrated heartily at the wedding feast and died of a blood hemorrhage in his sleep that night.

The Hun’s legacy

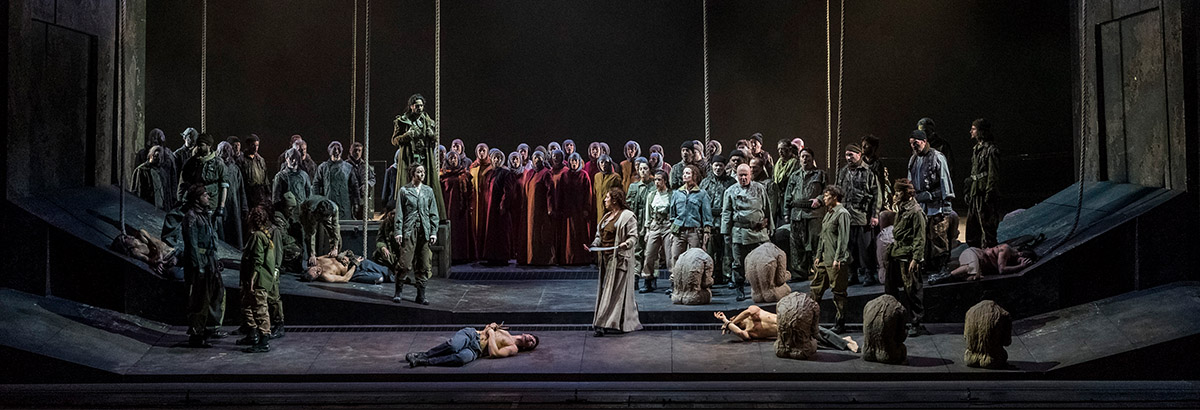

In both history and Verdi’s opera, Attila the Hun’s legacy lives on through art, both accurate and reimagined. Watch history and fiction come to life in Attila Highlights in Concert. Music Director Designate Enrique Mazzola leads world-renowned principal artists Christian Van Horn, Tamara Wilson, Matthew Polenzani, Quinn Kelsey, and members of the Lyric Opera Chorus in a performance of piano-accompanied excerpts from Verdi's early masterpiece, the story of the infamous "Scourge of God," his consuming desire for power, and his final downfall.