April 03, 2025

Conductor Conversation: Enrique Mazzola on "The Listeners"

Internationally known as a Verdi specialist, Music Director Enrique Mazzola also has a long record of commissioning and conducting new work. Here, he talks about the score of The Listeners — its mystery, its expressive power, and even its silences — and the many pleasures to be found in Missy Mazzoli’s music.

Howard (Kyle Ketelsen) guides the Listeners in a chilling ritual of synchronized spiritual harmony.

You previously conducted one of Missy Mazzoli’s pieces — These Worlds in Us, with the London Philharmonic. How did that come about?

It was during Covid, in a London without traffic. The desire was to make and record music, and also to make the sound visual. There was a wish to go beyond the silence of the period. I knew of Missy Mazzoli because of her connections to Chicago [Mazzoli is a former Mead conductor-in-residence at the Chicago Symphony Orchestra], but I didn't know her music yet. It was very interesting for me: These Worlds in Us is a very beautiful, very flowing, orchestral score. It was part of a small video series where we also did Dvorak’s New World, Sibelius’s Finlandia, things like that.

A very symphonic mix.

I really wanted to include Missy’s work — in part because I wanted to meet her artistically before we did her opera Proving Up, which I was going to conduct at Lyric in 2021. So we decided on These Worlds in Us. I love the score. It's full of emotions, full of rhythm, full of nostalgia, full of evocation. It's about 10 minutes long — a good introduction to a concert.

Lyric’s presentation of Proving Up was canceled due to the pandemic, unfortunately.

It was — but it is in the list of what I have in my repertoire. Like I have Traviata or Trovatore, I have Proving Up. I didn't perform it, but I was ready for the first day of a rehearsal. So I know the opera perfectly.

Maestro Enrique Mazzola leads the Lyric Opera Orchestra in a recent concert celebrating the life of his predecessor, Sir Andrew Davis.

And now you are deep into The Listeners. Can you describe characteristic traits in Mazzoli’s music?

Indeed. Both operas are quite dark, in a sense. There is mystery in both titles, about what is real and what is unreal — characters in Proving Up, and the Hum in The Listeners. In both operas, there is always a mix of very angular accents and sweeping lines of melody. The seen and the unseen. And also, in a way, the heard and the unheard.

That’s a very interesting observation, considering it’s live music!

We must never forget that we are in an operatic world. Actually, the silences in Missy Mazzoli’s music are as important as the music. They create superb tension. There’s a famous quote from Debussy about that — the space between the notes — and with Mazzoli it is very true. The things that you don’t hear just remain in the air, part of the mysterious world of this opera. I found that in Proving Up as well: I thought, OK, this is in the line of Orphée, Turn of the Screw, and Macbeth. There are apparitions — but the apparitions sing with a real voice.

It’s the operatic world, as you say.

One might say that there is a niche tradition of seen and unseen things in opera. In the banquet in Macbeth, there’s the famous scene where he drinks with everyone, and he suddenly sees a ghost sitting next to him. For all those gathered with him, there is no one.

This approach or element goes back a long way.

These things have always amplified people’s curiosity. Considering it from a compositional viewpoint, it’s rich with sonic possibilities. In The Listeners there's not really a supernatural world. It is more about an interior world, this feeling of hearing something that the entire world does not hear, and the fact that you feel cut off from society because you have this feeling. The hum is real in your mind, and you feel comforted by connecting with other people who have the same issue, but then this feeling creates problems between you and your family, you and the people you work with, you and society.

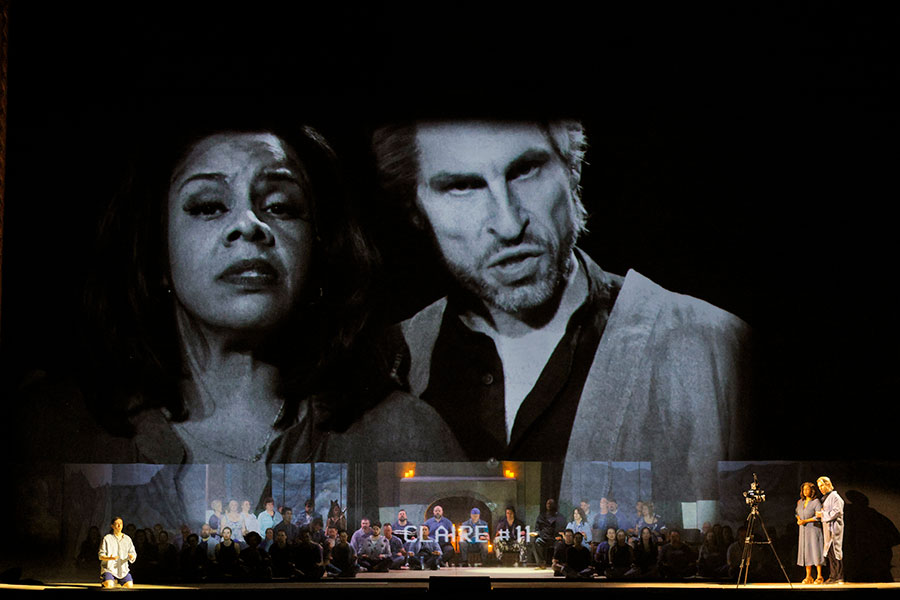

Claire (Nicole Heaston) is coaxed into accepting her place as Howard's (Kyle Ketelsen) devoted new number two.

You recently conducted a program of all Puccini. Is it different to conduct a contemporary sonic landscape like The Listeners?

Well, Puccini is fluid. Liquid. So the downbeat can be in the air, not set in stone or metal. I grew up with Carlos Kleiber's Bohème, which is one of the most liquid recordings of Bohème ever, probably. In contemporary music, the technique of the baton becomes much more — not severe exactly, but more strict, because there are a lot of changes of tempo. The construction of the phrase can be much more complicated than in Puccini, for example. A range of tempi requires a reassurance to the musicians that the baton is the tempo, so there is no liquid in the baton. The new tempo, let’s say, is written in stone. Also, because there is very often a percussion instrument, or a very specific articulated, complicated rhythm in the strings, there must be a firm hand. That said, there are pages of The Listeners on which there is a beautiful flowing horizontality. Also, let's say in Puccini, very often there is a coincidence of the singing phrase with the first note of the orchestra. We start together. Very often in Mazzoli’s music, the starting of the phrase is not connected to the orchestral phrasing. The style is a little bit unsettling, which very much makes sense in this work.

Does that mean the music-making is more difficult?

Of course it is. Missy Mazzoli scores are not easy scores. Her palette in the orchestra is really wide. And in the two operas I have explored deeply, there is extensive use of the extreme colors — for example, in the very high frequencies of the violin, or the very low notes of the trombones or double basses, so that we have a wide sonic spectrum. Another characteristic that I find in her work is what I call columns in the score. What I call for myself colonna. There is action, action, action, action. Then double lines. Everything stops. Fermata. And then a singer, free. A capella. You see it in the score; it stops flowing. Then she will introduce a group of notes, which melt into a second group of notes, and then she comes back to the first. It's very gravitational.

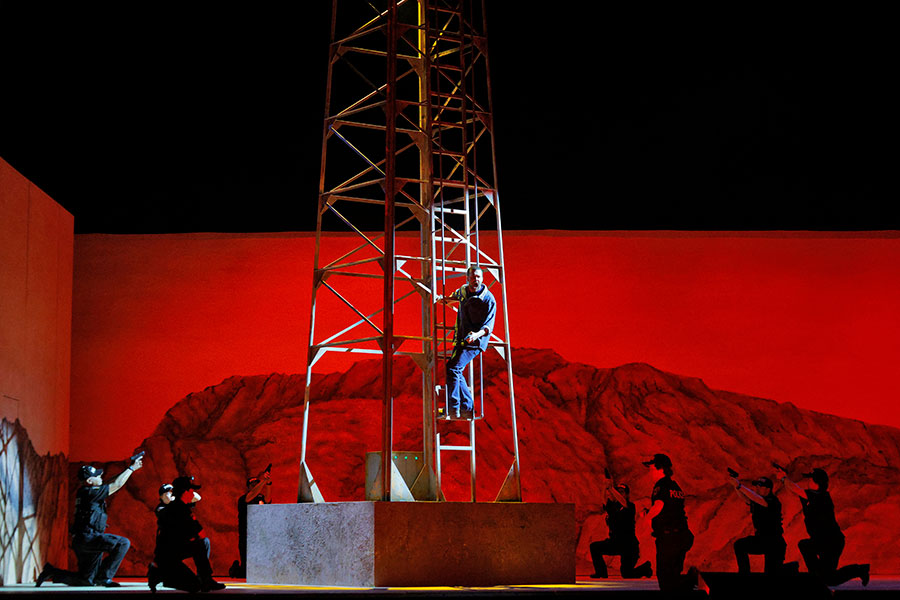

Dillon (John Moore) is surrounded by the police as he attempts to destroy a mobile tower that he believes is causing the 'hum'.

Are you saying that it becomes heavy?

No — it’s the attraction of the group of notes. In a way we could say it is tonal, but it would be very reductive to say that Missy Mazzoli is a new tonalist. It’s more that I find the gravitational forces of groups of notes becomes a style.

It's not a pull back to a certain key, but it's a pull to a foundation of some kind.

Which also makes for an eerie and dark atmosphere, because there is a note, and then there are variations of the note. A sharp to this note, a flat to this note, a third to this note, a seventh to this note, and the seventh then reaches the octave. And we feel a gravitational pull. Sometimes it's groups of notes that attract all the others, or first separate them, and then they attract. This is the tonality of Missy Mazzoli. But it's always difficult to enter into these analyses, because the composer may disagree. She could say, Okay, no, this is not my stuff. This is my own interpretation.

Is this the sort of thing you’ll be talking with her about?

The rehearsal period is the best time to discover a score with the composer. I remember during Champion last season with Terrence Blanchard, he was sitting in all the orchestra rehearsals just behind my left shoulder, and every two or three minutes he would whisper something in my ear: I would prefer that like this, or Go, go, go, go. It’s fantastic. Better than looking at a score together is to have the music out loud. To do it with the composer next to you is really a fantastic experience.

Claire (Nicole Heaston) and the Coyote (Rachel Harris) discover that they are not so different from one another.

And what kind of experience will The Listeners be for our audiences?

People coming to The Listeners will probably have the usual questions: Oh, it's a new opera. Let's see what this is about. What does it sound like? But this type of opera raises hundreds of questions about our society. One might say, this is the big answer to the question of why we do opera today. In today's world, we need opera to raise questions that can be uncomfortable outside the opera house.

And yet this work is not Fidelio, or Dead Man Walking, about “political” topics.

You're absolutely right. We are not speaking about the death penalty, or discrimination. But a work like this, even without being political, is political in a way. Even Traviata, if you will, is political. The main thing is, this opera is filled with spectacular moments of energy and expansion. I can’t wait to start.