April 23, 2021

Richard Wagner and the journey of the RING

The influence of Richard Wagner (1813–1883) is evident in the tone poems of Richard Strauss and the film scores of John Williams, and spreads beyond composition into philosophy, literature, the visual arts, theater, and film. Wagner's poetic lines are scattered throughout James Joyce's Ulysses, the bard of the American prairie Willa Cather's The Song of the Lark, the architecture of Louis Sullivan, the drawings of Arthur Rackham and Jean Delville, and some pretty memorable cinematic moments, including those in Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now. Friedrich Nietzsche described Wagner as "a volcanic eruption of the total undivided artistic capacity of nature itself," and Thomas Mann hailed him as "probably the greatest talent in the entire history of art." Wagner's four-opera Ring cycle, Der Ring des Nibelungen—of which Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods) is the finale—stands as one of the hallmarks of 19th-century culture.

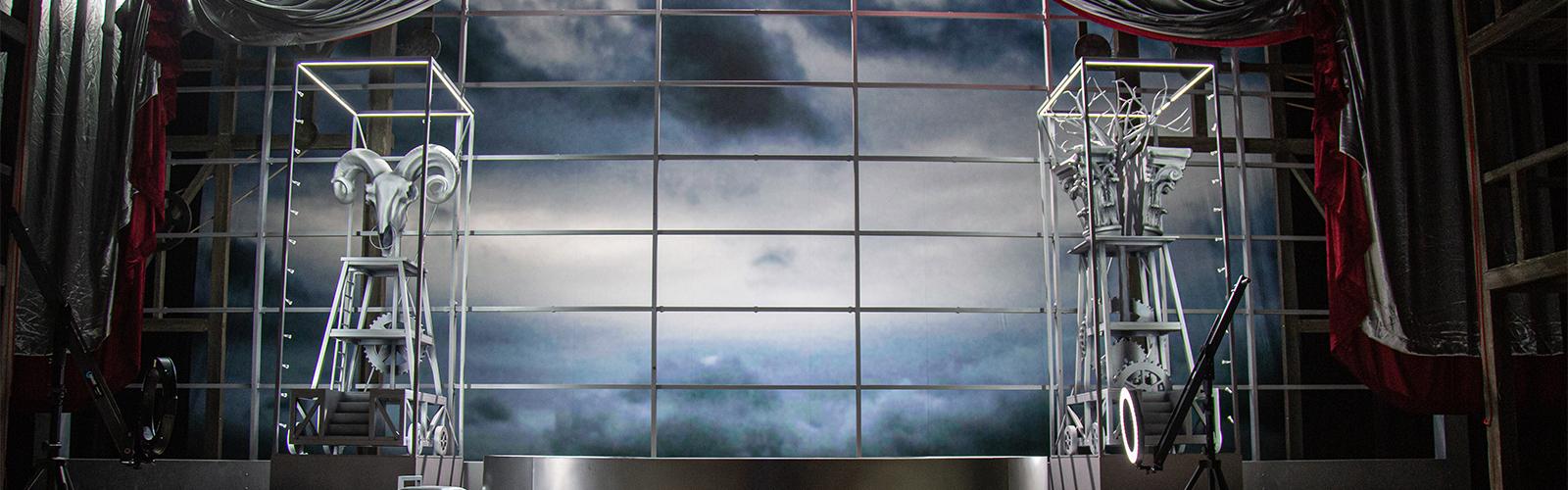

Wagner's epic Ring cycle begins with Das Rheingold, seen here in Lyric's 2016/17 production.

We often refer to the "lives" of Wagner, not merely to indicate the many hats he wore, but also the variety with which he and others told his story. He was a prodigious "re-worker" of his own life's tale. His second wife, Cosima (the daughter of Franz Liszt), journaled daily during the last quarter of his life, capturing the composer's every move and thought, though her journals regularly include annotations in Wagner's own hand. His life was one of definition and redefinition. It is fitting, then, that a question mark hovers over the paternity of one whose work resounds with parental unavailability. His "official" father was the police actuary Carl Friedrich Wagner, but the boy's adoptive father, the actor-painter Ludwig Geyer (who adopted the child on Carl Friedrich's death in November 1813, when Wagner was just six months old), was likely his biological father and was, in all likelihood, at least part Jewish—a fact Wagner did not discover for another fifty years. All the same, Geyer's presence in Leipzig's theater scene left an indelible mark on the young Wagner, and his childlike mixture of determination and invention would not dim throughout his life.

Wagner received only a small amount of formal education in music and composition, learning largely on the job. At the age of 19, he began a series of seasonal engagements conducting at various minor theaters, giving him the opportunity to craft a first operatic attempt, Die Feen (The Fairies), in 1834, and then a second, Das Liebesverbot (The Ban on Love, based on Shakespeare's Measure for Measure), two years later. But on these positions alone he could not support the comfortable lifestyle he craved. Escaping his creditors, he spent two impoverished yet formative years in Paris, then the center of the operatic world. Wagner was received there by the composer Giacomo Meyerbeer—the father of French grand opéra and a whole new school of operatic thought—who later provided Wagner influential letters of introduction to the Dresden Court Opera. It was there in 1842 that Wagner's Rienzi was premiered, followed shortly thereafter by Der fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman) and Tannhäuser. By then, the impressions of his traveling years had solidified into dogma: that the Italian and French-dominated operatic genre lacked a solid German counterpart.

Photograph of Richard Wagner, taken when the composer was in Paris for the premiere of Tannhäuser in 1861.

In the early months of 1848, Wagner was busy finishing Lohengrin. The world outside his studio, however, was on fire. The February Revolution in Paris spilled into the streets, ending the constitutional monarchy and establishing the French Second Republic. Spurred by their francophone allies, the March Revolutions across the 39 independent states of the German Confederation secured (at least for a time) the first freely elected parliament for all of Germany. As soon as Wagner set down the final effervescent A-major chord of Lohengrin, he marched into the streets—with both his feet and his pen.

Wagner was introduced to utopian-socialist ideas and supported the democratically led republican movement. He believed the revolution would bring about a thorough democratization and renewal of society, yield a unified German nation-state, and enact basic reforms in the sphere of culture and the arts. His support of the provisional government and participation in the information service of the Dresden insurgents, however, forced Wagner to flee a warrant for his arrest, and he would live in exile in Switzerland for a decade.

Alberich (bass-baritone Samuel Youn) wields the cursed ring of power in Lyric's 2016/17 production of Wagner's Das Rheingold.

Under the influence of the revolution in 1848, Wagner conceived of the fable that he later set as his music festival The Ring of the Nibelungen, the intellectual content of which was based on the concepts of "true socialism" and dealt with the struggle of humanity against the rule of gold. It would be a "total work of art," a Gesamtkunstwerk. What Wagner envisioned was a new type of opera, a rebirth of the art form, costumed in a distinctively German guise. Coming out of his revolutionary years, his aesthetic goals were, from the beginning, shot through with nationalist zeal, which verged on the pseudo-messianic and xenophobic. His vision for the artwork of the future was intended to establish opera—or "music drama" by this time, distancing it from the "opera" of his Italian and French predecessors—in a radically recast form, as at once the instrument and the product of a reconstructed society.

Wagner believed to his core that a corrupt industrial society could only be reformed through education and by reconnecting the people with an ideal natural state. By marrying together music, drama, poetry, painting, and more, the total work of the Ring could absorb its spectators, transporting them to a different reality. Telling the story of civilization—from the primordial E-flat undulations at the beginning of Rheingold to the immolation and flooding of the world at the end of Götterdämmerung—the Ring is about nature and ambition in conflict, and a "primordial equilibrium," as English philosopher Sir Roger Scruton writes, that can only be recovered "if our human dominion were relinquished." Overcoming the will of power demands sacrifice of a kind that only love can accomplish. That is what the Valkyrie Brünnhilde—who has, through compassion, fallen into the human world and fallen in love with Siegfried—finally accomplishes through her self-sacrifice. In a baptism of fire she rearranges the world and atones its sins.

Soprano Christine Goerke as Brünnhilde in Lyric's 2017/18 production of Wagner's Die Walküre.

Whether Brünnhilde's death returns us to the natural order or whether that order is even desirable are questions the Ring does not answer. Wagner believed that modern people, having wavering faith in the divine order, need another route to meaning, to spiritual and moral fulfillment. He turned to music drama, and in particular the Ring, as a vision of the ideal achieved with no help from the gods of Valhalla—a total work of art that can, in the proper context, express our deepest mortal longings. A total work of art that bewilders our senses while tussling with our better angels.

Wagner was a revolutionary, active on the barricades, with his pen in journalism and polemics, and through his endless melodies and vision for an artwork of the future. But he was also largely a synthesizer—a reinventor. Many of his ideas were not necessarily novel; they just had disparate origins, and Wagner brought them together. His life—or lives—could be defined by any number of -isms: democratic-republicanism, nationalism, nativism, illusionism, realism, dilettantism, chauvinism, antisemitism. . . Wagnerism. He was friends with kings and an enemy of bureaucrats. He was one-time confidant to and then longer-time enemy of Nietzsche, vacillated in his adulation of Arthur Schopenhauer, memorialized neo-pagan Christian traditions, and read widely on Buddhism. He was discussed by Karl Marx, John Ruskin, and Leo Tolstoy, and inspired Hugo Wolf, Anton Bruckner, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Edvard Grieg, and Camille Saint-Saëns—all of whom were among the first Ring audiences. He was a fallible individual whose influence is still felt in the art and culture we regularly encounter today.

Austin Stewart is an arts administrator and musicologist. He received his PhD in historical musicology from the University of Michigan. His program notes have been printed by the Aspen Music Festival and School, Opera North (UK), the University Musical Society, and the Ann Arbor Symphony Orchestra. AustinStewart.com

The program notes for Twilight: Gods were commissioned by Michigan Opera Theatre with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Twilight: Gods

Twilight: Gods

Experience an original film that captures Lyric's sold-out Chicago premiere of Twilight: Gods, a reimagining of the final chapter of Wagner's epic Ring cycle.

Filmed during the live production at Millennium Park Lakeside Garage in Spring 2021, this unique, drive-through experience was conceived by director Yuval Sharon, who wrote the new English texts, and features poetic transitions written and performed by Chicago interdisciplinary artist avery r. young. Chicago filmmaker Raphael S. Nash has created this original new feature from the critically-acclaimed production and it showcases the performances, video work and installations brought to life by singers, instrumental groups, and actors.