April 09, 2020

Siegfried's Sabbatical

Richard Rothschild of Oak Park has written about opera for more than 30 years, including during a 21-year stint at the Chicago Tribune.

Of the myriad musical marvels that flow from Richard Wagner’s Ring des Nibelungen cycle, one of the most significant takes place shortly after the midpoint of Siegfried, the third opera in the tetralogy.

It’s not a musical moment. Indeed, it’s anything but a moment. Between finishing work on Act Two of Siegfried in the summer of 1857 and starting Act Three, Wagner took a bit of a break – a 12-year break.

How long is 12 years? Consider these diverse historical examples: approximately the length of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s three-plus terms as president, or as long as Voyager 2’s Grand Tour of the outer planets between 1977 and 1989. It’s more than one-third of poor Mozart’s short life and the number of full seasons Michael Jordan was a member of the Chicago Bulls.

Wagner nearly stopped composing the opera shortly after Siegfried skewers the treacherous Mime and sits exhausted in the noonday sun under a linden tree. In a letter to Franz Liszt, Wagner wrote, “[Siegfried] will be better off there than anywhere else.” The composer eventually finished Act Two on August 9, 1857, and then departed the world of the Ring until 1869.

Why did Wagner stop work on a project that had dominated his creative life since 1848, the year he wrote the libretto for Siegfried’s Death (which later became Götterdämmerung)?

Certainly crushing financial troubles played a role, stemming from Wagner’s inability to stage the two previous Ring operas. Das Rheingold was not given its world premiere until 1869, Die Walküre not until 1870 (both were composed in the 1850s). And the composer, who often had his next operatic project well in view, was starting to fall under the spell of Tristan und Isolde. By 1859 the new opera was complete, although Tristan would not enjoy its debut performance until six years later in Munich. And there was more on Wagner’s plate: in 1861 he revised his earlier opera Tannhäuser for a new production in Paris, described by one opera historian as “one of the greatest operatic flops of all time.” When Wagner had the audacity to place the Venusberg ballet right after the overture, the French were outraged, including the august Jockey Club swells who booed vociferously throughout the entire opera. Tannhäuser closed after only three performances, and Wagner never returned to Paris.

Finally, there was that minor piece of business at decade’s end called Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Wagner’s only comedy of his mature operas.

An amnesty from King Ludwig II served as a pardon for Wagner’s role in the 1849 Dresden Uprising, making the composer no longer persona non grata in Germany. Wagner set up shop in Munich, this time with a new wife, Cosima von Búlow, the daughter of Liszt and former wife of conductor Hans von Bülow (Wagner’s first wife, Minna, had died in 1866). Wagner’s affair with Cosima had been one of the worst-kept secrets in Europe, yet von Bülow still agreed to conduct the world premieres of Tristan in 1865 and Meistersinger in 1868.

When Wagner finally returned to Siegfried, he was simply a different composer. The groundbreaking harmonic and rhythmic structures of Tristan – one of the most influential compositions in the history of music – had carved a permanent place in Wagner’s creative imagination. Act Three of Siegfried is new, certainly in a musical sense.

“When listening to Siegfried Act Three we sometimes wonder if we are listening to Tristan instead,” wrote the late British musicologist Derrick Puffett:

When listening to Siegfried Act Three we sometimes wonder if we are listening to Tristan instead

It is almost as if we have been listening to two different operas, two different Siegfrieds composed before and after Tristan. After the pastoral fun and games of Acts One and Two, we are plunged back into the world of myth…the world of Rheingold and Walküre; and the musical expression of that world is the familiar stock of leitmotifs, incomparably intensified through their contact with Wagner’s new harmonic language.

Act Three of Siegfried, which Wagner completed in 1871 (the premiere took place as part of the first complete Ring cycle at Bayreuth in 1876), is not superior to the first two acts, just different. In their magnificently comprehensive text A History of Opera, Carolyn Abbate and Roger Parker wrote that “Wagner’s taste in harmonies and sonorities grew stranger and more complex in the 1860s and 1870s.”

Indeed, from Tristan on, much of Wagner’s music begins to display a plaintive and at times even a haunting quality, one that began with the five Wesendonck Lieder composed during late 1857 and early 1858. And listen to the moment when Brünnhilde recognizes her horse Grane in Act Three: for a few measures, with the horns playing so tenderly, the music seems to foreshadow Richard Strauss, as if Brünnhilde were channeling her inner Marschallin.

As for the plot, there are no new significant twists to the opera after Act Two, and the character of Siegfried doesn’t really change. Just as the teenage hero’s deeds drive the action of the first two acts with the forging of the sword Nothung and the slaying of the dragon Fafner, he will dominate the narrative in Act Three, culminating with the awakening and wooing of the onetime warrior-maiden Brünnhilde.

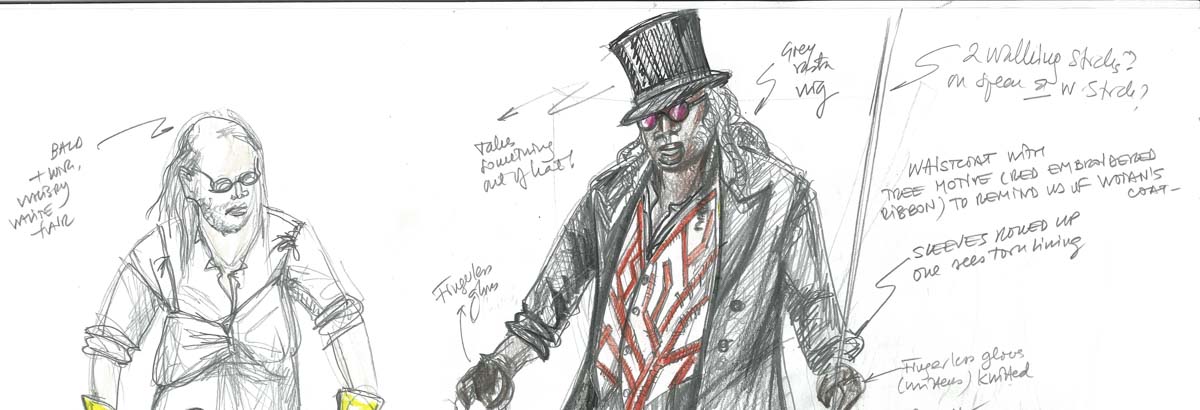

Costume Sketch, The Wanderer and Mime

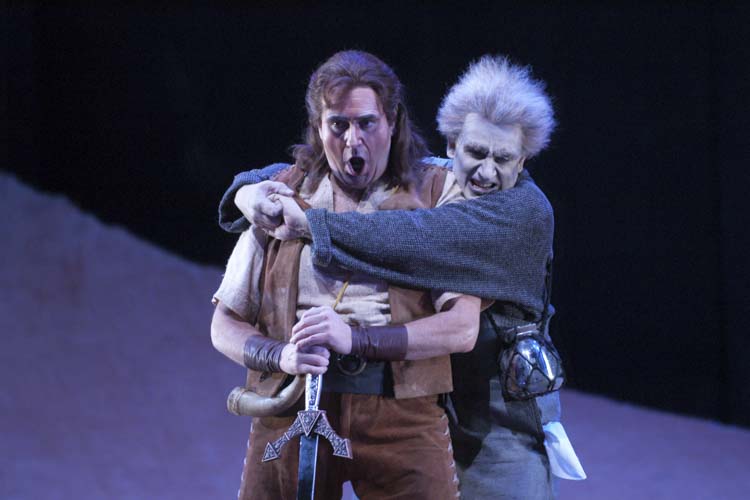

John Treleaven and David Cangelosi

Wotan, one of the two or three most important characters in the entire Ring cycle, remains a supporting player. In the guise of the Wanderer, he is more of a commentator on the opera’s ebbs and flows rather than a controlling force – the former star athlete who now sits in the TV booth. Once Siegfried splinters his spear early in Act Three, Wotan’s presence in the Ring is over.

The “pre-Tristan” portion of Siegfried contains numerous treasures. The forging scene that closes Act One is music communicating an energy and verve that seldom appear in the Ring’s earlier operas. Lord of the Rings fans will note the similarity of Siegfried reconstructing his father’s broken weapon to what happened when the shards of Narsil were remade for Aragornas the mighty sword Anduril, Flame of the West. J.R.R. Tolkien, author of the literary trilogy, borrowed liberally from Wagner.

Act Two of Siegfried is one of Wagner’s most creative enterprises, a darkness to light musical odyssey. It begins with sounds of menace and foreboding from the drums and tubas, what the composer called “Fafner’s Repose.” The deep forest is not a place for beginners. Midway through the act, however, the mood shifts as the beautiful “Forest Murmurs” section – seemingly Wagner’s response to Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony – is quietly introduced by the higher strings and woodwinds.

Once Siegfried slays the slow-moving Fafner (who resembles an aging heavyweight fighter who hasn’t faced a legitimate challenge in years), the forest sounds as liberated as Berlin did the night the Wall fell. The Woodbird sings with great joy that Siegfried “will own the Nibelung hoard…and if he desires to find the Ring, it will make him ruler of the whole world.” And the Woodbird’s advice for Siegfried to beware of Mime sets up perhaps the most inventive musical sequence of the act: Mime’s words, which have been accompanied by a scherzo-like tempo reminiscent of Schubert’s “Death and the Maiden” string quartet, turn much slower, as if allowing Siegfried to ascertain their true meaning. Mime is toast.

The act concludes as the once-quiet “Forest Murmurs” burst with noontime energy. Instead of soft woodwinds, a triumphal trumpet and the full orchestra escort Siegfried out of the woodland and toward the “wondrous woman who sleeps on a high rock.”

After 12 years Wagner did not return to the Ring with subtlety or restraint. The start of Act Three finds the composer throwing open the doors and windows to Haus Ring (so to speak) and clearing out the dust and cobwebs with a new sense of mission. Erda’s music, so slow and mysterious in Das Rheingold, is urgently dramatic as Wotan seeks advice one final time from the “eternal woman.” Few acts in all Wagner begin with so much pace and power.

The late Wagner biographer Robert Gutman viewed the Wotan-Erda scene as a turning point, calling it the composer’s “emotional and sad farewell to the complete artwork; music drama now gives way to grand opera, the genre in which Götterdämmerung was originally conceived.”

...music drama now gives way to grand opera, the genre in which Götterdämmerung was originally conceived.

And following the dramatic confrontation between Siegfried and Wotan and Siegfried’s monologue after he has conquered the magic fire, grand opera is what transpires with the Siegfried-Brünnhilde duet that closes the work. For the first time in the Ring, two characters actually sing to one another simultaneously. In the rapturous duet that closes Act One of Die Walküre, Siegmund and Sieglinde, Siegfried’s parents, had taken turns pledging their love but their voices never joined. Tristan und Isolde, with perhaps the most famous of all love duets, provided Wagner the foundation for combining voices.

As with the brother-sister romance of Walküre, the power and beauty of Wagner’s music overshadows the fact that Brünnhilde – as Anna Russell famously reminded us – is Siegfried’s aunt. It’s a romantic connection Game of Thrones aficionados might recall from the passionate scene between Jon Snow and Daenerys Targaryen that ended the most recent season of the blockbuster cable series. Of course, Brünnhilde knows she is Siegfried’s aunt and doesn’t care. (Daenerys, the Mother of Dragons, doesn’t realize this inconvenient truth – at least not yet).

Perhaps the best-known music of Act Three is the lulling passage sung by Brünnhilde that forms the central theme of Wagner’s “Siegfried Idyll.” As the onetime Valkyrie contemplates her new life as a mortal woman, the music turns more introspective and intimate, a welcome change of pace from the scene’s romantic tension.

For all his boyish charm and courage, Siegfried never really sees the big picture. He tells Brünnhilde, “My mind fails to grasp far-off things.” Siegfried can come across as limited or even, dare we say, ignorant. Götterdämmerung, the Ring’s final opera, will show this heroic lad is not the master of all situations (John Culshaw, who produced the first complete recording of the Ring cycle in 1958-65, said of him, “Wisdom is not, and never will be among his attributes”).

Whatever his faults, the confident and joyously happy Siegfried closes his eponymous opera wearing a beautiful, shining new musical mantle. Wagner’s 12 years away from the Ring truly paid major dividends.

Photo: Dan Rest