April 10, 2020

Die Walküre: A Tug at the Heart

Call it the great exception.

Die Walküre, the second opera of Richard Wagner’s mammoth Ring of the Nibelung cycle long has reigned as the most popular of the tetralogy and ranks among the favorites of the composer’s entire oeuvre. Wagner is challenging to many operagoers, but even those devoted to more compact, more obviously tuneful Italian and French standard-repertoire works often make room for Die Walküre.

Why? Because in Die Walküre, particularly its closing pages, Wagner showcased his better self, and composed music for the ages.

The opera introduces audiences to Brünnhilde, the Ring’s central character and the opera’s namesake. Die Walküre features a rapturous love scene in Act One, one of most famous tunes in all music, “The Ride of the Valkyries,” plus a finale that, when it comes to heartrending beauty and eloquence, has few equals in opera.

“The Ride of the Valkyries,” painted by W. T. Maud (1865-1903).

And considering that between the end of Das Rheingold and the opening of Walküre the god Wotan has sired at least eleven children (none with his wife, Fricka), there are noticeable biographical elements to the work, particularly Wagner’s less-thanfaithful relationship with his wife.

When Wagner composed Die Walküre between June 1854 and March 1856, his marriage to Minna Planer was disintegrating. Minna often criticized Wagner’s wandering eye, most notably his relationship with Mathilde Wesendonck, the wife of a wealthy silk merchant who was a patron of Wagner’s.

By the time Walküre had its world premiere in Munich on June 26, 1870 – featuring the real-life husband and wife duo of Henrich Vogel and Therese Vogel as Siegmund and Sieglinde – Minna had died. Wagner was about to marry Cosima von Bülow, with whom he already had produced three children. Cosima was the daughter of Franz Liszt and the wife of maestro Hans von Bülow, who had conducted the world premieres of Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger.

But Die Walküre’s appeal extends well beyond memorable music and an interesting back story. It takes patience to mine Walküre’s treasures, musically and dramatically. Much of the opera is foreboding and confrontational. The music, often in minor keys, bespeaks strife, debate and anger. Yet audiences for nearly a century and a half have been more than willing to wait for the opera’s grand payoffs.

Why?

Because these are characters we care about, particularly Siegmund, Sieglinde and Brünnhilde. Even Wotan, who came across as a bossy wheeler-dealer for much of Das Rheingold, the opening opera in the cycle, draws our sympathies by time the curtain falls. David Pountney, who is directing the four Ring productions for Lyric Opera of Chicago, sees elements of Ibsen, surely in advocacy of women’s rights and identity, spotlighted in his play A Doll’s House.

Rheingold, despite its fast-moving action and musical glories, doesn’t register on the same personal level as Walküre. Drama and power politics abound but other than Alberich’s grubby pursuit of the Rhinemaidens and the giant Fasolt’s high school-like crush on the goddess Freia, Rheingold provides little space for love or humanity.

An audience of Wagner's time would have seen costumes like these in Die Walküre.

Walküre more than fills the gap, starting with the romance between the Volsung twins, Siegmund and Sieglinde in the opening act. Act One is a gem of a mini-opera. It is the shortest act in the Ring, lasting a bit more than an hour, with only three characters— all who are gone by early in Act Three. Symphony orchestras around the world perform concert versions of Act One, and the 1935 Act One recording with Lauritz Melchior as Siegmund, Lotte Lehmann as Sieglinde, and Emmanuel List as Hunding, with Bruno Walter conducting the Vienna Philharmonic, is considered one of the greatest operatic performances ever put on disc.

Siegmund is the Ring’s man of constant sorrow and his Volsung motif indicates a proud warrior who has had to fight for everything. Once he meets Sieglinde, he senses that his life could be about to change. Yes, there’s that little matter about the two being brother and sister. Most audiences, however, are willing to cut the Volsung kids a bit of slack. Their relationship doesn’t have the “ick” factor of brothersister lovers Jamie and Cersei Lannister in Game of Thrones.

Carolyn Abate and Roger Parker, authors of the authoritative A History of Opera, suggest Siegmund and Sieglinde “jolted Wagner to a higher plane in his thinking about motifs in the dark, those intricate musical transformations that depict the twins’ increasing passion.” The authors note the Volsungs’ realization that they are related seems “to ignite them further.”

The act hits overdrive when Siegmund pulls Wotan’s sword Nothung out of the ash tree and the orchestra explodes in triumphal light with the themes of the sword and the Volsungs, culminating one of Wagner’s most rapturous love duets. Too bad Die Walküre doesn’t end with the happy pair escaping into the night. Even an illegal marriage seems preferable for Sieglinde than staying with that boorish bully Hunding.

Act Two, the second longest of the cycle (after Act One of Götterdämmerung), challenges singers and listeners. It returns to the musical and dramatic darkness that pervaded the start of the opera with a different set of relationships. Wotan and his favorite daughter Brünnhilde, who open the act in high spirits, will be in bitter conflict when the curtain closes. Wotan’s ability to control events – even in his own family – is shattered, starting with his wife Fricka, the goddess of the hearth and matrimony.

A strict constructionist when it comes to matrimonial matters, Fricka demands that Wotan disavow the immoral Volsung union. Audiences often view Fricka as a righteous spoilsport, but Valhalla law is on her side. Her music ends with a noble reference to her “rights, sublime and glorious,” showing Fricka, too, is an immortal, and Wotan’s equal.

As Wotan’s plans disintegrate, for the first time in the opera we hear the music of Alberich’s curse – Walküre is the only opera in the cycle where we never physically see the ring. The confident and sometimes arrogant god of Rheingold is losing his mojo. In front of Brünnhilde, Wotan delivers a lengthy narration, described by music critic Alex Ross as “the most spectacular psychological tailspin in the history of opera.” The quiet, contained music accurately portrays Wotan’s utter dejection as he realizes the fates of the ring, the gods and, certainly, the Volsungs are out of his hands.

For the rest of the Ring cycle, this is a humbled god.

Brünnhilde, who comes off as spirited but somewhat one-dimensional through the opening of Act Two, undergoes her own transformation in the “Todesverkündigung,” the announcement of death to Siegmund, who no longer enjoys the Valkyrie’s protection. It is a scene of majesty and foreboding. The music starts at a stately pace with the Valhalla theme, but it increases in tempo and agitation when Siegmund tells Brünnhilde that he will not accompany her to the joys of the afterlife once he learns his “sister-bride” Sieglinde will not be at his side.

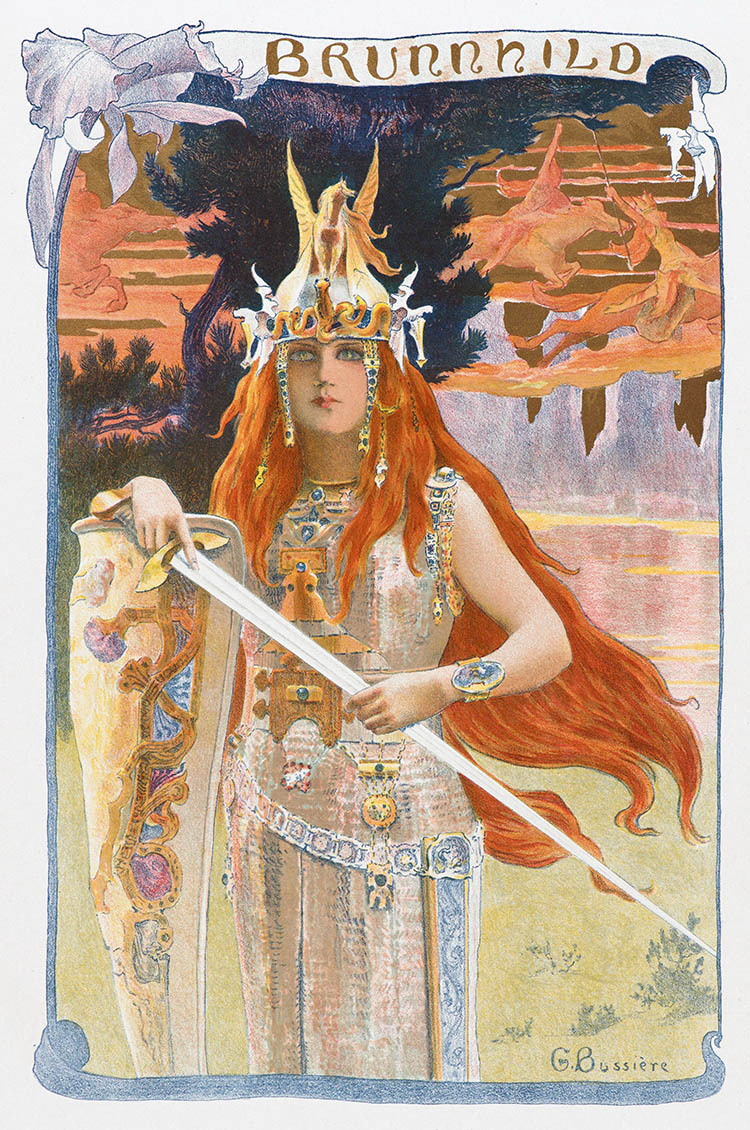

The heroine of Die Walküre, extravagantly depicted by Gaston Bussiere in 1897

Brünnhilde, who has never witnessed such romantic passion and humanity, has a profound change of heart and agrees to fight at Siegmund’s side, culminating a powerful scene that, ultimately, results in Wotan’s favorite daughter forfeiting her rights to be a Valkyrie. But if Brünnhilde has lost Wotan’s support, she has become a more sympathetic – dare we say human – character.

Before getting into the crux of Act Three, a quick word about “The Ride of the Valkyries” that opens the act, perhaps the most famous music Wagner ever composed. It is accessible enough to serve as a ditty for Elmer Fudd as he pursues Bugs Bunny, but it also possesses the martial quality to accompany a battle scene in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. As Wagner unleashes the full power of his large orchestra, audiences can picture winged horses soaring over mountaintops, ridden by a very different kind of woman.

To mid-19th century sensibilities, the presentation of women as confident and athletic as the brash Valkyries would have been radical. Females didn’t behave this way. Fricka dismisses the brood as “goodfor-nothing wenches.’’ Yet the Valkyries are the predecessors not only of a superhero like Wonder Woman, but the worldclass female athletes who win Olympic and NCAA championships. Perhaps their music has become a bit of a cliché but the Valkyries’ attitude was more than a century ahead of its time.

Wotan is never angrier than when he confronts Brünnhilde in Act Three. She is his favorite daughter, the only Valkyrie to whom he would confide his innermost thoughts, the one he allowed to “serve me mead at my table” and who protects his back in battle. Now she has betrayed him. But because of their special relationship, the humiliated Brünnhilde senses her father still regards her dearly. Once she persuades “warfather” to surround her with flames so that “only a fearless noble hero will find me,” the ultimate glories of Die Walküre are released.

Had Wagner not written another opera, he would be remembered for Wotan’s farewell, music of tremendous emotion that accompanies this most conflicted of fathers who must say goodbye to his beloved daughter. The swelling music leaves the strife behind and begins to incorporate elements of Valhalla, the Valkyries, the sleep motif, the coming of Siegfried in the next opera and, eventually, Loge’s magic fire theme, called by some wags the “heat motif.”

Long gone are the pyrotechnics of the Siegmund-Sieglinde love duet, replaced by music of profound tenderness. Any father who seen a daughter leave home, be it for college, work or marriage, knows the emotion that accompanies such partings.

“On a happier man may your eyes shine,” sings Wotan as music from the strings and horns sends Brünnhilde into a magical sleep. No doubt, Wotan is diminished from the master of the universe he sought to portray at the start of Die Walküre. Yet he is a far nobler character. Through unexpected and tortuous paths, Wotan, now a sympathetic father, has earned our respect and admiration, and his farewell brings a glorious benediction to this most beloved of Ring operas.

Richard Rothschild of Oak Park has written about opera for more than 30 years, including during a 21-year stint at the Chicago Tribune. One of the first operas he attended was Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman at the original Metropolitan Opera House in New York.