April 09, 2020

Singing and Acting the RING

Onstage the Ring cycle offers tremendous artistic rewards to its performers. Below the leading artists of Lyric's Ring discuss the challenges of their roles.

Tanja Ariane Baumgartner

Fricka in Das Rheingold, Die Walküre

Waltraute in Götterdämmerung

“Fricka is the keeper of the old order,” says the German mezzo. “Although in Rheingold she’s softer, more loving, she’s still reminding her man to stay on the right path, while in Walküre she doesn’t only remind him — she tells him the harsh truth, severely and adamantly. She’s come to a turning point. I think of her final words: the honor of the whole family must be restored.”

In Lyric’s Walküre, “we show that Fricka is suffering, struggling. What she’s doing is actually very honorable. I also think she’s a loving wife. In her first scene with Wotan in Rheingold, we have some moments of love, whereas in Walküre they aren’t coming together anymore.” In Lyric’s production “it was more about my longing for his love. She even opens her jacket, as if she were more vulnerable, but it doesn’t work — he isn’t interested.”

Vocally speaking, “Walküre is more furious, faster, also a bit louder, than Rheingold, with more breakouts to the upper range.” As with all the Wagner mezzo parts, Götterdämmerung’s Waltraute asks for “a voice where all the registers are pretty strong. Waltraute is Brünnhilde’s empathetic sister, first of all. Here again, she’s trying to solve the whole story — this is what she and Fricka have in common.”

Burkhard Fritz

Siegfried in Siegfried And Götterdämmerung

The German tenor considers himself a quick study, “but Siegfried is musically so complicated that learning and memorizing took at least three months. Then, letting it settle down in the body took over a year. You have to get used to some very unexpected harmonic changes and some strange jumps in the notes.”

Onstage it’s important to make clear that “the young Siegfried really has no idea what the world is.” In Lyric’s production Fritz enjoys “playing the kid with Mime, having the huge hammer and anvil, and forging the huge sword. The dragon scene is so beautiful — and so funny! And the duet with Brünnhilde is something to look forward to.” Ultimately, Fritz hopes to show “the journey Siegfried goes through from being an inexperienced child to being a young, totally enflamed lover.”

The Götterdämmerung Siegfried has the challenge of “trying to make the audience believe that he is not changed within himself. But something has changed him to do all the things he’s does there, betraying Brünnhilde and marrying Gutrune. At the beginning of the first act of Götterdämmerung he’s still so restless — there’s so much of the restless child in him: ‘I can do everything and fight everybody, I just want to go out into the world.’ He’s like a teenager trying to find the power in himself.”

Christine Goerke

Brünnhilde in Die Walküre, Siegfried, Götterdämmerung

The Walküre Brünnhilde is essentially “a mezzo role with a couple of high notes,” says the American soprano. The middle voice is especially vital in the opening of the final scene with Wotan, “which is so stark and also so plaintive at the same time.” Goerke loves embodying this Brünnhilde’s youthfulness (“she’s a serious tomboy”). In the final scene “Brünnhilde is upset, but she still loves Wotan. I’ve always said this is the great love story of the cycle. Although she loves Siegfried, that was never the same kind of connection — two halves of the same being.”

Brünnhilde’s music in Siegfried lies higher, which helps to characterize her: “Where I place my voice in that tessitura creates a more silvery color. Wagner gives you something completely different in the lyricism and the joyful exuberance.” The soprano relishes showing Brünnhilde’s apprehension when wooed by Siegfried. “For someone who’s been so brave as a Valkyrie to find this as frightening as she does — that’s a big step, and such a human reaction.”

The Götterdämmerung Brünnhilde is Goerke’s favorite. “I liken it to Fiordiligi in Così fan tutte, which sounds crazy, but it’s got the two-and-a-half octaves, it requires agility in places, and the ability to sing a very lyric line high up or down low.” In the characterization, “it’s amazing to see the culmination of everything that her soul drives her towards. In her we see her father’s fury, but also her mother’s wisdom.”

Alan Held

Wotan in Die Walküre, Siegfried

Wotan in Siegfried is older than in Die Walküre. His music is also much slower, more evenly paced — that is, until Act Three, where he finally goes crazy vocally in the scenes with Erda and Siegfried. The role generally lies higher as well, and the Act-Three orchestration is fuller than just about anywhere else in the Ring except for the “Ride of the Valkyries”!

In Walküre, Wotan does a lot of talking and tries to push the action, whereas in Siegfried he’s responding to other people’s words, as in his scenes with Mime and Alberich. That’s the secret of any Wagner role to me — you have to be an active listener.

In his scene with Brünnhilde that concludes Die Walküre, Wotan realizes that his world is done. Then, in Siegfried, he’s trying to hold onto any little bit of dignity and power he might once have had. When he tests Siegfried, he knows he’s going to lose the battle, and that there’s now a special hero who can take on Brünnhilde. He’s challenging Siegfried; when you have kids, you don’t want everything to come to them so easily! You want them to be tested, so they can then face everything that lies before them.

I try to make my Wotan very human. Even though he’s a god, he still has human emotions. In the Walküre monologue, that’s a real man talking about real feelings and real ambitions. He’s not talking as a god — he’s talking as a defeated man.

Brandon Jovanovich

Froh/Das Rheingold; Siegmund/Die Walküre

Froh is “simply a counterpoint to the giants,” says the Montana-born tenor. “I’m there to protect my sister and support the family.” Onstage Froh does a lot of listening, and it’s vital to Jovanovich that he listen actively: “If you don’t have something living in your brain, if you’re not constantly thinking, you become a black hole that detracts from the opera.”

Siegmund is “something of a roller-coaster ride, with so much raw passion, but I find that the emotions can sometimes make things easier to sing. You have to be aware of where the limit is, but the exciting part in any role is going up to the border and occasionally maybe crossing it.”

The music occasionally stretches into baritone territory. In college, my first role was for bass,” Jovanovich recalls. “Now, in rehearsal, I sing down the octave if it’s early in the morning — I sound like a bass-baritone. I find that I can utilize that register, and I think that does have an effect on the way I’m able to sing, especially in some of the lower parts of Siegmund.”

Much of Siegmund’s music is simply conversation. When Jovanovich doesn’t have movement that he can pour his emotions into, “it all goes internal. It’s in my mind, my body, the idea of being positioned by fate, by the gods — there’s no way I can get around it.”

Matthias Klink

Mime in Das Rheinngold, Siegfried

Many singers deliver much of Mime’s music in a so-called “character voice,” but the German tenor declares that with any role, “I always try to stay with my own voice. I never try to be something else. The challenge with Mime is always to follow what the music demands, but not at the cost of the voice.” When Mime tells Siegfried that he should treat him better, “with all that whining, just see what Wagner actually wrote: you can sing it in a beautiful way. Of course, there are typical character moments where he spits out the words, but if it’s just ugly, it’s not interesting! I like when you can walk on the edge — then it’s something that really counts for the listener.”

The character is “looking for his power. He’s not a healthy person, but he seems to me also a victim of the story itself. This makes him more interesting — just being mean without an inner state of being. In Das Rheingold, where Mime gets beaten up all the time, we see what being Alberich’s brother is like for him — their relationship is so full of hatred and aggression. Mime always tries to be more intelligent than Alberich, but he’s the loser, which makes him maybe more sympathetic.”

Štefan Margita

Loge in Das Rheingold

“Loge is a wonderful role,” enthuses the Slovak tenor, “both in the music and character, both being very colorful. There are portions that one can certainly sing legato, including all of the second scene. It’s important to use different colors to express what Wagner wished, and to do it through the character based on what there is in the text.”

This is a lengthy role and delivering Wagner’s very dense abstruse language can be daunting. “That´s why it´s vital to speak German well and strengthen it through expression, so that you are understood also by the audience who may not speak the language.”

Margita characterizes Loge as “a likeable schemer, able to orient himself to any situation. As a demigod, he also has human character traits which other gods fail to understand, and that results in him winning them over.” Is his treatment of Alberich genuinely cruel? “I guess so, but that’s the revenge toward Alberich for hurting others.”

The tenor enjoys Lyric’s Rheingold because “it’s fantastic and playful, with an amazing cast and a brilliant director.” In 2016|17 at Lyric, Margita was able to establish terrific rapport with his colleagues, Eric Owens and Samuel Youn — “they are both amazing.”

Ronnita Miller

Erda in Das Rheingold, Siegfried

First Norn in Götterdämmerung

In Erda’s music the American mezzo doesn’t think about trying to make the sound darker or lower, or about bringing out contralto colors. “Instead, I think of the low notes quite high, because I never want to dig. If you do that, you can’t sing those tricky intervals, particularly in Siegfried.” Erda’s music can be energized through the weight of the text, “and by showing an undercurrent of intensity.”

In many productions it’s challenging to characterize Erda onstage, “because the movement can be restricted. Everything else is moving, and then you have this person who must grab attention while not doing very much. It’s like when you have a busy area, like an airport or a mall: you can hear elevator noise, people talking, but when you hear a child’s voice, it rings out over everything. Erda has to have that sort of power. She doesn’t have to do anything, but you hear her and you pay attention.”

Of the three Norns, “people say the First Norn is the oldest — she speaks of past events and how they affect her right now. I find her a little easier than Erda, because there’s so much more orchestral texture under her. The lines are quite long and legato — you can luxuriate in them.”

Stephen Milling

Hunding in Die Walküre

Hagen in Götterdämmerung

“You can’t compare Hunding and Hagen,” says the Danish bass. “Hunding is more one-dimensional — there aren’t so many aspects to show. It’s short, and a dramatic bass can sing it when he’s fairly young. I waited to sing Hagen until I was 50! It’s a tough role, and a long one.”

Hunding, says Milling, “isn’t polite, isn’t nice to his wife, and is very demanding — he likes being in charge.” With Hagen, Milling appreciates the many beautifully composed passages “where he can sing softly and inwardly. We have a lot of the dark side of him. After all, he was raised to hate the gods, and the only reason he’s in the world is to bring them down. In the scene with his father Alberich, he doesn’t recall any happiness from his childhood. But onstage you can also show that he actually cares about Gutrune — he has a soft spot! It gives the role more color, while also making his scariness even bigger.” Milling enjoys the Act-One monologue, “where he ends up sitting there practically laughing and saying, “I have everything in my hand and I can just squeeze.”

Brian Mulligan

Wotan in Das Rheingold

Gunther in Götterdämmerung

Most of Wotan’s music feels like recitative, although he does have some beautiful legato in the two arias when he’s talking about Valhalla. He’s in control, the self-assured authority figure. He has fleeting moments of “How are we going to figure this out?”, but the over-arching feeling is that this is a lark -- just another little jam that he’s gotten himself into -- to entertain himself. But when Erda comes out of nowhere and confronts him, he has kind of an existential crisis and for a few pages he’s in dumfounded disbelief. This is maybe the first time he’s felt something real in thousands of years!

Vocally Gunther lies slightly higher than Wotan, which is more middle voice. In Lyric’s production, Gunther is very much under Hagen’s control from the beginning. I like to play him as a virgin — someone who’s been waiting for the perfect woman to marry, but she hasn’t come along. Or it could be the other way around: maybe women have been rejecting him. He’s inexperienced, with no confidence, but he’s trying to be the head of the family — he needs to be married and have children. Then, when Gunther listens to Siegfried describe his life and his love for Brünnhilde, it’s like he asks himself, “How have I inserted myself into something so perfect and pure as the holy alliance between these two people?” In the next scene, he’s trying to protect the dead Siegfried’s body and keep the ring from getting into Hagen’s hands. In that moment, he acquires some backbone and redeems himself.

Elisabet Strid

Sieglinde in Die Walküre

The Swedish soprano views Sieglinde as “a storytelling role — you have to put a lot of effort into the text. Just to sing it with a beautiful big voice makes it less interesting. To tell the story in a way that people can understand is important. And of course, you must live the character. When you step onstage you’re not just singing Sieglinde -- she takes over your voice and your soul.”

It’s vital to show onstage that, while grateful to be away from Hunding, “Sieglinde lives with the horror that he’ll come back and try to get her. At the same time she feels freedom and love with Siegmund. Her mind is a bit torn apart, almost like a psychosis, since she’s lived in a horrible environment for so long. It’s that inner feeling that something bad will happen to destroy her happiness.”

Strid strives to communicated “a longing for freedom, love, and peace. Then she finally has the gift that is Siegfried, even though she doesn’t survive to see him. But she knows she’s carrying him forward, and I’m filled with so much euphoria, so much love, at that moment. She’s carrying the future — her unborn son, this treasure she has from Siegmund. She grows as a character as she realizes what real love is.”

Samuel Youn

Alberich in Das Rheingold, Siegfried, Götterdämmerung

In Lyric’s Ring, the three Alberichs have all been role debuts for the Korean bass-baritone. “People speak of it as a difficult role, but for me it’s actually been quite comfortable, although, of course, you need a good vocal technique and your acting ability must be utilized to the full.”

Alberich isn’t a role associated with legato singing, but Youn feels “it’s absolutely possible to bring beautiful legato to Alberich’s music — for example, in the third scene of Rheingold, when he’s with Loge and Wotan.” Although the Götterdämmerung Alberich is Youn’s role debut, “I’ve sung both Hagen and Gunther previously. Alberich’s scene with Hagen is really a key moment; he doesn’t sing much, but without this scene you can’t explain the rest of the opera.

Showing Alberich’s humanity is important. He’s always feeling inferior and, in many respects, jealous. The ring is his only hope.”

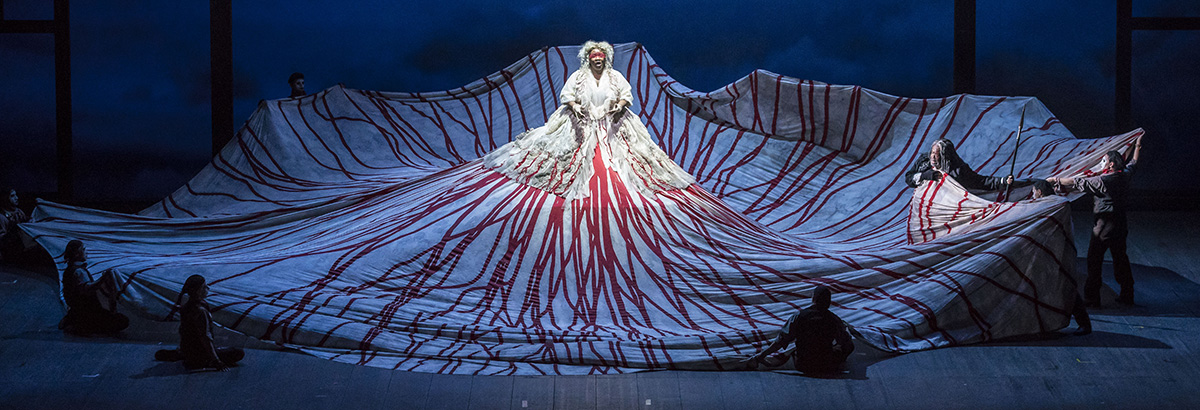

In Lyric’s Rheingold, Youn relishes the first scene with Rhinemaidens, “with the platforms and the big machines. And in the third scene, Alberich’s jacket is made out of money, with golden stripes. In European productions he doesn’t become so rich so quickly! The difference David Pountney made in the character was like from zero to a hundred. I think it’s great that Alberich becomes so fabulous!”

Edited from interviews with Roger Pines, Dramaturg, Lyric Opera of Chicago.

This article was written for publication in the Ring cycle program, 2019/20 season.