November 15, 2023

Donizetti’s conquest

The critics panned the composer’s glittering comedy — but he won the hearts of Paris.

‘Monsieur Donizetti seems to treat us like a conquered country; it is a veritable invasion. One can no longer speak of the opera houses of Paris, but only of the opera houses of Monsieur Donizetti.’

Hector Berlioz’s newspaper review of the first performance of Donizetti’s The Daughter of the Regiment (La fille du régiment) at Paris’s Opéra-Comique on February 11, 1840 set the work in the context of the many other productions of the Italian’s operas then dominating the city’s houses. The carping and unpleasantly nationalistic note struck by the great French composer was echoed by other critics: The opera was facile and unconvincing, plagiarized, too noisy, too disjointed, too Italian (and for others, not Italian enough), merely a big “bag of candies,” and so on.

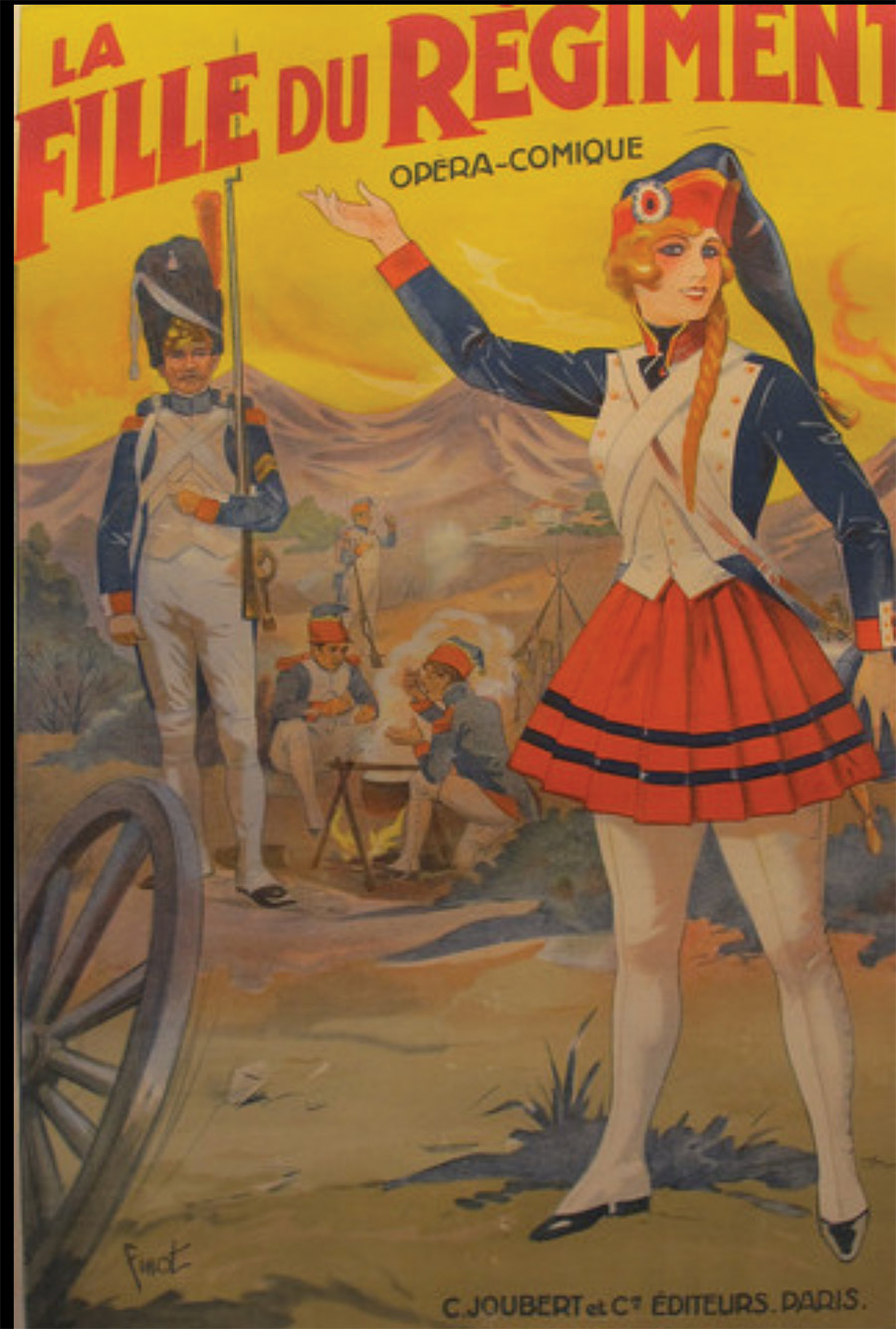

The Daughter of the Regiment poster, by Emile Finot, for a 1910 production in Paris.

Happily, The Daughter of the Regiment survived this early barrage of criticism — in style. The French public disregarded Berlioz and his acolytes, warmly welcomed the Donizetti “invasion,” and was pleased to count itself among the Italian’s “conquests.” The sparkling opera was to become one of his most popular works in France over the course of the nineteenth century. From 1848, it entered the Opéra-Comique’s repertoire, and it stayed there until 1916. In 1914, on the eve of the World War I, it celebrated its 1,000th performance.

Part at least of The Daughter of the Regiment’s popularity across France, moreover, lay in its brazen display of patriotic national fervor. This was particularly evident in the stirringly militaristic “Salut à la France” (“Long live France”) sung by the eponymous heroine Marie, an orphan born to the sound of cannon-fire and adopted by France’s 21st “La France” Regiment. In the 1840s, the French government still associated Rouget de Lisle’s 1792 Marseillaise with rebels and critics. Before the Marseillaise was adopted as the official national anthem in 1879, festive national celebrations on July 14 often involved the performance of Marie’s “Salut à la France.” The custom declined (along with Donizetti’s reputation) in the early twentieth century, but in a notable exception, the Franco-American soprano Lily Pons sang the aria at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in 1941, draped in a tricolor flag bearing the Cross of Lorraine emblem that Charles de Gaulle’s Free French had adopted for national Resistance against the Nazis. It was the diva’s Casablanca moment. Donizetti can hardly have imagined such a trajectory for what he called “his little opera,” but he certainly intended The Daughter of the Regiment to flatter French sensibilities and national pride.

The Paris production of Lucia di Lammermoor in 1837 had brought him new commissions and the popularity in Paris that Berlioz so resented. But The Daughter of the Regiment was the first of his many operas to be world-premiered in the city, and the composer was aware that its success would consecrate his talent, crown his whole career, and open the road to fatter fees and more commissions. After all, Paris was the world capital of opera: The city boasted an enviable ensemble of opera houses and troupes, a very large, knowledgeable, and cultivated audience for opera, and a music press that offered dozens of informed reviews of new work. If composers or performers could make it there, it was generally held, they could make it anywhere. Donizetti had been angling for a Parisian commission from the mid 1830s. Though he remained a restless composer who, in the words of an admirer, “writes like a steam-engine and lives half his life in a coach,” the city remained his main operating base until his death in 1848.

Donizetti’s careerist calculation came off. His 1840 apotheosis elevated him to the status of Parisian celebrity; he was recognized in the street and received endless invitations from fashionable society. Among other successes, Lucrezia Borgia and his final triumph, Don Pasquale, followed. In time, he came to tire of “the courtesies, the dinners, the portraits, the plaster busts” of polite society, but the world he inhabited was altogether more salubrious than the drafty garrets of Puccini’s La Bohème. Moreover, after the peevish censorship that his work had incurred in conservative Naples, he also found the air of intellectual freedom for which Paris was famed refreshing and invigorating.

Donizetti soon recovered from any hurt he felt from the initial criticisms of The Daughter of the Regiment. He took heart from the fact that virtually all his reviewers, critical or otherwise, acknowledged that the opera lay outside the Italian protocols that had dominated Donizetti’s music thus far and was clearly recognizable as a genuine comic opera in the French style. That had been his aim — to make of the work, as one of his kinder reviewers noted, a successful application for French naturalization.

Lily Pons triumphed as Marie in the Met’s 1940/41 Season.

Donizetti chose as principals two young French singers at early stages in what would prove illustrious careers. Juliette Bourgeois (who had changed her name to Borghese while touring in Italy) played Marie, while the tenor Marié played Tonio, her Italian suitor. The choice proved only half-successful. Reviews were loud in praise of Borghese’s looks, voice, and acting, but united in panning Marié, who was said to have sung off-key all night. (It is interesting, if excruciating, to imagine quite how he mangled the eight high Cs in the “Ah! mes amis, quel jour de fête” aria for which the part has become famous.)

Donizetti’s strategizing over other aspects of the production was more effective. He employed two very experienced and highly rated librettists based in Paris, with an ear for changing public moods. They delivered him a risk-averse piece: a classic Romantic love affair, complete with Italianate color and the mandatory happy ending. Admittedly, The Daughter of the Regiment’s plot was lightweight and predictable. At the first night, the coup de théâtre by which Marie was revealed to be the daughter of the aristocratic villain of the piece was greeted by a heckler proclaiming,”That was obvious!” But as Donizetti’s librettists knew, comic opera never lets predictability get in the way.

Donizetti also played to his audience’s prejudices by orienting the opera’s plot around past French military glories associated with the expansion of France in northern Italy under Napoleon’s First Empire (1804–15). This was all the more pertinent in that patriotism was very much in the air at that moment. An international crisis over Egypt in 1839-40 triggered a war scare that led the government to call up troops and fortify defenses around Paris. The Orleanist king Louis Philippe, set on the throne by the 1830 Revolution after the overthrow of the reactionary Bourbon dynasty, positioned himself as a liberal patriot, resisting conservative forces at home and abroad.

The year 1840 also witnessed a flaring up of pro-Napoleonic sentiment. Louis Philippe regarded Napoleon not as the creator of a rival dynasty but rather as a great French patriot and conqueror. The king sought to capitalize on the Napoleonic Legend that had grown up around the ex-Emperor since 1815 in ways that would buttress his own regime. To this end, he took the initiative of getting Britain to agree to the return of Napoleon’s ashes from Saint-Helena where the British had confined him in his last years. In a hugely spectacular ceremony in December 1840, the ex-Emperor’s remains were interred in the Invalides.

The setting of the hyper-nationalistic The Daughter of the Regiment in Napoleonic Italy had personal resonance for Donizetti: It was where the composer was born and bred. He was born in the city of Bergamo in 1797, a matter of months after it was incorporated into the pro-French Cisalpine Republic, one of the so-called “Sister Republics” that Napoleon had set up all over the Italian peninsula after his brilliant Italian campaigns of 1796–97. The region would later be incorporated into the kingdom of Italy, a key part of the transnational Napoleonic empire. In 1815, Donizetti’s elder brother volunteered (like Tyrolean Tonio in the opera) for service in Napoleon’s Grand Army.

The bravura performances of Joan Sutherland and Luciano Pavarotti (shown here in 1973) cemented the opera’s popularity in the U.S.

Given these connections, Donizetti must have followed the return of Napoleon’s ashes with great interest. Reports of the day’s ceremonies highlighted the presence, wearing their old, threadbare uniforms, of many so-called grognards (“old grunters”), that is, veterans from Napoleonic armies. Since the 1820s, the grognard had become a stock type in the literature, popular songs, engravings, and caricatures that had burnished the Napoleonic Legend among the French people. Though still a serving officer, Donizetti’s Sulpice is very much in the literary grognard mode. Heroine Marie, for her part, was modelled on the related stereotype of the vivandière. Such women, selling troops tobacco, alcohol, and other petty commodities to supplement army rations, and adopting laundry and nursing duties, had a history going back well into the 17th century. But they were particularly numerous in the Napoleonic wars and reputed for acts of patriotic valor and devotion. Ex-vivandières rubbed shoulders with Napoleon’s grognards in the watching crowds.

Threatening to thwart Tonio and Marie’s happy ending are forces both international and domestic. On the one hand, the French army removes the heel of reactionary Austrian and Bavarians rulers — represented in the opera by the Germanic-sounding Marquise de Berkenfield — over the Italian peasantry. The latter warm to French conquerors who have brought them “land, culture, and equality,” and they look to benefit from the confiscation of aristocratic lands, including the Marquise’s manor-house. They feel comfortable with the fraternal, egalitarian backslapping of the French soldiery, which shocks the Marquise, who confesses to regarding as “nonsensical, absurd, and preposterous” the democratic ideal of the common people governing the state.

The conflict of values between the Tyrolean ruling classes and the French patriots is most clearly evidenced in the singing lesson that the Marquise administers to a very resistant Marie. The song at issue is not a Germanic Lied, moreover, but a French poem and melody. Yet it is of an out-of-date, whimsically artificial sort that Donizetti’s bourgeois opera audiences would have associated with the old French aristocracy. Music comes to mirror the Marquise’s progressively comical failure to produce a veneer of gentility in an increasingly rebellious Marie. The winsome simpering ditty is drowned out by the marches and fanfares of trumpets, trombones, and drum-rolls of the French nation in arms. The music thus underlines the moral: Following one’s heart is always to be preferred to social promotion into the hide-bound aristocracy, and a noble heart will always trump a noble escutcheon. So Marie gives up high heels for army boots, abandoning her German, aristocratic, and anti-democratic mother so as to remain under the protection of her adoptive father, the 21st “La France” Regiment — and thus, more broadly, of her fatherland.

With The Daughter of the Regiment, Donizetti gave the French public what he thought it would like to hear, as a shrewd but effective means of ensuring his own Parisian consecration. It showed a receptive audience that French patriotism could be seen and felt and sung — and all the better in the context of a successful love story. In that respect, Donizetti took a leaf out of the book of an earlier itinerant composer keen to make his mark in the Parisian opera world, namely, Mozart. In The Marriage of Figaro as in The Daughter of the Regiment, “tout finit par des chansons” — a fact that all lovers of happy endings and great operas will strongly approve.

Colin Jones is Emeritus Professor of History at Queen Mary University of London and Visiting Professor at the University of Chicago. His many books include Paris: Biography of a City (2006).